One of the first places the Protestant Reformation caught on was in Switzerland—especially in Zürich. Within a few years, the teachings of the Reformation reached Geneva—a city that had the will to reform, but lacked a strong leader. That leader fell into their lap in 1536, when a Frenchman named John Calvin fled to Geneva to avoid persecution in France. His teachings and writings not only transformed the city of Geneva, but much of the world.

Because Geneva welcomed refugees from all over Europe, when these refugees went back to where they came from, they helped re-make the churches in their home countries according to Calvin’s theology. So not only was Switzerland changed, but also places like Scotland, the Netherlands, many places in Germany, and much of Hungary. The Calvinist influence on the early Church of England was much stronger than most of us realize these days.

None of these churches called themselves Calvinist churches, of course. They were usually just called Reformed. So John Calvin’s writings have come to be the basis of what’s called Reformed theology. Many people associate Calvin and Reformed theology with a single concept: Predestination. But the truth is that Calvin wrote relatively little about predestination, and it’s not talked about that much in Reformed churches. Instead of predestination, Reformed churches talk a lot about the grace of Jesus Christ and the sovereignty of God. In fact, to believe in God in Reformed churches is to believe that God really is the Ruler of creation. And it’s through this lens that we read the most well-known verse in today’s scripture lesson:

By grace you have been saved through faith, and this is not your own doing; it is the gift of God.

—Ephesians 2:8

So God’s love comes to us not because we’ve worked for it and earned it, but simply because we believe in it. And our faith isn’t something we’ve come up with on our own, but is itself a gift freely given. To a Reformed believer, this is the heart of the gospel of Jesus Christ.

Both of this church’s denominations (the UCC and the Disciples) have their roots in the Reformed tradition—the DOC in frontier Presbyterianism, and the UCC in both the Congregational churches and the German Reformed Church. And it’s from the German Reformed tradition that I want to tell you a story.

A century after the Reformation took hold in Europe, there was a young Calvinist pastor in Germany named Joachim Neander. He was much loved for both his preaching and his hymns. (We even sang one of them at the opening of today’s worship service.) He ministered to a little town that was located where the tiny Düssel River emptied into the mighty Rhine. The town’s name was Düsseldorf, or Düssel Village. And though today it’s one of Germany’s biggest cities—and the capital of its most populous state—back in the 1600’s it was maybe about the size of Chardon.

Pastor Neander loved his people and they loved him back, but sometimes he needed to get away. And so he’d hike up the Düssel valley and find a place to commune alone with God. He was probably going by the words of Jesus:

Come away to a deserted place all by yourselves and rest a while.

—Mark 6:31

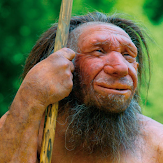

Though Joachim Neander died of tuberculosis before he even reached the age of 30, he was long remembered in that area. And the gorge of the Düssel River began to be called Neander Valley. When factories started to be built, natural resources needed to be exploited, and so this valley fell victim to mines and quarries, and was destroyed. None of its natural beauty, remained. And one of the consequences of this destruction is that many things that had been buried for thousands of years were exposed. Among them, the bones of an ancient people who were a lot like humans, but were still different. Scientists named them after the place they were found—Neanderthal (German for Neander Valley)—and that’s how a German Reformed pastor came to share his name with what we call cavemen.

A few decades after Neander’s day, the first German Reformed Christians arrived in North America. They made their new home in Pennsylvania, but after the American Revolution, they—like just about everybody else—began to head west. By the mid-1800’s, there was dozens of German Reformed congregations here in Ohio, and so they founded their own college in Tiffin. They named it Heidelberg College.

Heidelberg College was named only indirectly after the city of Heidelberg, Germany—home to a world-famous university. It was the theological faculty of that university that wrote a document that has had more influence than any other on Reformed believers over the centuries. It’s called the Heidelberg Catechism, and it came out in 1563. And it’s after this catechism that Heidelberg College got its name.

Neither the Disciples nor the Congregationalists made much use of catechisms, but they’re found in many (if not most) other Christian traditions. They’re manuals on faith, taught through questions and answers. Catechisms were taught at home by parents, and one of the pastor’s duties was to examine the youth of the church on their knowledge of the catechism. The Heidelberg Catechism consists of 129 questions, and kids had to memorize the answers in order to be confirmed as members of the church.

It might sound foreign to us, but this was the way it was done in the old days. And this particular document—the Heidelberg Catechism—was the way the Christian religion was introduced to millions of children from the Netherlands all the way to what is today the far west of Ukraine. That’s because the people in that corner of Ukraine are mostly Hungarian speakers, and most of them belong to the Hungarian Reformed Church—a church that in the U.S. is part of the United Church of Christ. In much of the world, catechisms are no longer required. But among Hungarian speakers, the Heidelberg Catechism is still a big deal.

I spent part of my sabbatical with the Hungarian Reformed Church back in 2013. Most of that time was spent in Transylvania (today part of Romania), and I have another story I want to tell you about how a church that many of us don’t know much about changed history.

Our graduates were nowhere near being born yet, but I dare say most people in this room remember the year 1989 very well. Before then, much of Eastern Europe had been in the grip of communism since the end of World War 2. This was a simple fact, and most of us didn’t expect it to change in our lifetimes. But suddenly, one by one, every communist dictatorship began to fall. And every one of them fell peacefully. With one exception, that being Romania. There was no sign of change in Romania, and it appeared that their communist dictator—a man named Nicolae Ceaușescu—was going to hang on into the future.

But another man—one nobody had ever heard of—did something he shouldn’t have. Hungary now had freedom of the press, and this man gave an interview on Hungarian television. He was himself a pastor of the Hungarian Reformed Church in Transylvania, and his name was László Tőkés. In that interview, he criticized the communist government of Romania. And as punishment, they tried to force him out of his church in a city called Timișoara. The people of his congregation surrounded his house to protect him, and soon non-Hungarian people joined in. This was just about a week before Christmas in 1989. And by Christmas Day, the protests had spread and Ceaușescu was deposed. And it all started with a pastor who spoke his mind—a pastor, by the way, that if he were in the United States, would be part of the United Church of Christ.

When I can get away with it, I usually just wear a jacket and tie instead of vestments in worship. But I have two kinds of robes: one German (I’ll tell you a little about that one next week) and one Hungarian—that’s the one I’m wearing now. It’s called a palást, and it’s what virtually every Hungarian Reformed pastor wears. And I told you the story of the 1989 Romanian Revolution not just to show how a Christian speaking the truth to power can make a difference, but also because it was László Tőkés himself who put this cape on my shoulders.

So that’s my brief introduction to the Reformed tradition. And every Sunday during this series, we’re going to do an act of faith together. Today’s act is the first question and answer from the Heidelberg Catechism…

—©2023 Sam L. Greening, Jr.